What's grief got to do with it?

by Lennon Flowers

A few months ago, a funder asked how our experience with grief informs our work now.

I paused. I flashed back to another conversation with a different would-be funder in the pluralism sphere, years before. Trust Labs’ work grew out of what was then the partnerships team at The Dinner Party. I worked for years to convince people that interrupting the isolation that attends grief can help us to interrupt the isolation that’s animating our politics. I failed. “I don’t get what grief has to do with it,” said that funder at the time. We didn’t get that grant. After struggling to make the case to our staff, our Board, and our supporters, we decided to split the organization into two. And thus Trust Labs was (eventually) born.

Our work today has to do with helping communities move through hard moments without breaking apart. On the face of it, that might have little to do with grief. But when you know to look for it, you begin to see grief and its effects everywhere.

Which means: In today’s world, exercising relationally sound leadership requires being grief literate.

Grief in the era of polycrisis

We typically think of grief as the natural product of losing someone significant to us. It is that, but it’s a lot of other things, too. Grief is the emotional reaction to the experience of loss. We can grieve all kinds of losses: of a job or a home or our health, of a relationship, of stability or security, of routines, of a future that's no longer within our reach. Grief is experienced not just individually, but collectively, in response to histories of discrimination, targeted violence, and inequities in everything ranging from healthcare to housing. Some forms of grief are referred to as “disenfranchised,” meaning they’re often deemed “less than” or unimportant or not real. In The Wild Edge of Sorrow, Francis Weller describes the "Five Gates of Grief," which captures everything from the grief we feel over the love we longed for and never got, to the grief we feel for the outcast parts of ourselves, to climate grief, to the grief passed down over generations. (I used to think all of that sounded hokey. Then I read it. I was wrong.)

These days, we find ourselves constantly on edge: Grief seems to permeate everything, all the time.

We’re living in what’s been called “the era of polycrisis,” in which multiple disasters fuel each other relentlessly, leaving all kinds of compounding effects in their wake.

A crisis is anything that exceeds our window of tolerance. In the era of polycrisis, our stress responses are constantly firing. That leaves us less resourced to meet the relentless challenges that continue to come down the pike. When things erupt in one arena, it’s often because we can’t tolerate what’s being asked of us in another. For any leader right now, de-escalation – and the ability to hold grief erupting in one arena while moving forward in another – becomes a thing of paramount importance.

The Four Rs

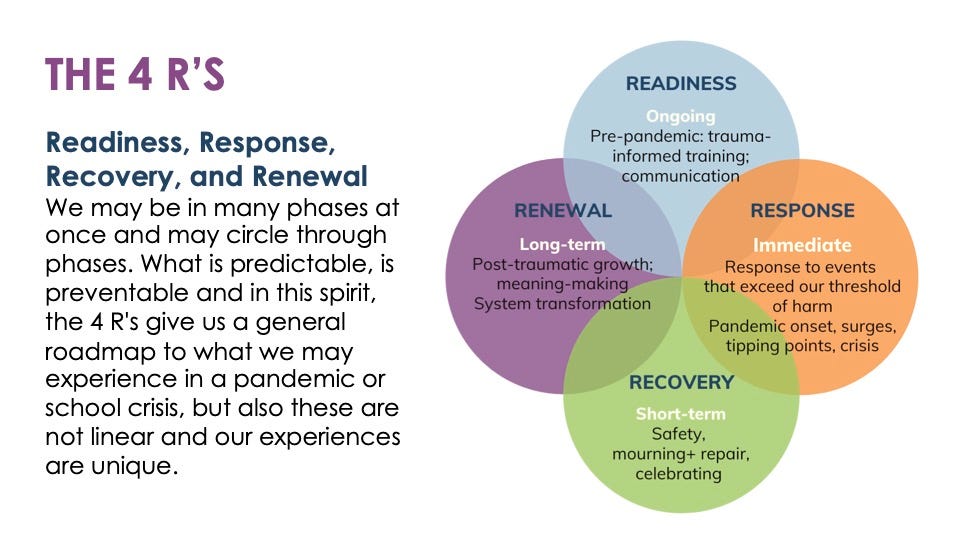

A framework I find helpful for responding to crisis comes from our partners at the School Crisis Recovery & Renewal project. Building on similar models, they cite 4 Rs of crisis response: Readiness, Response, Recovery, and Renewal. Designed to support educators navigating increasingly high-risk environments, the 4Rs demonstrate the entanglement between grief, leadership, and crisis response, and how to put grief literacy to practice.

Let’s start with Readiness: When there are things happening outside your control, you want to be able to access predictability where you can, by having policies and protocols in place. You want to know who to call when you need help, because you already trust them. You want to be able to hold spaces for ritual or meaning-making or other support that are familiar and part of your existing cultural DNA. You want to have thick relationships that can withstand acute stress responses and highly charged situations, and work through repair on the other side. All of that depends on the things you do before you’re in crisis.

Ever been force-fed a “moment of silence” or a seemingly supportive gesture that feels empty? Most people have pretty good BS-detectors, which is why it’s critical to norm pauses, reflection spaces, and a culture of care into your ways of working, before you need to call on them.

Strong social networks can even lessen the impact of a tragedy, by curbing preventable deaths to begin with. Researcher Eric Klinenberg famously showed that, in the face of a devastating heat wave in Chicago in 1995, mortality rates were significantly higher for those who lacked deep social ties. If isolation can kill, then trust-building can quite literally save lives (grief prevention, anyone?).

That helps to explain why pre-existing social connectedness and social cohesion lead to greater resilience in the face of crisis.

Which means: Grief prevention, grief care, relational leadership, and trust-building are inherently bound up with one another. Whether you're talking about a workplace, a congregation, a school community, or a family unit, our ability to navigate grief and trauma – and the crisis that often precedes it – is shaped by the norms and relationships in place before the crisis hits.

If you want to move through crisis with less scar tissue, you have to scaffold relationships and a reparative culture long before. For many, of course, the problem is that there's no longer such a thing as "before": To live in a polycrisis means having to build trust at precisely the same time that trust is fraying. We must do the work of scaffolding relationships even as we simultaneously work to stop the hemorrhaging.

Which brings us to that second R: Response. Crisis response is about mitigating harm wherever possible, and quickly deploying resources and assistance where they need to go. It's the "R" we tend to be most familiar with, so I won't belabor it here. In the face of a death, we’re quick to write the card, send the flowers, and make sure someone has the time off they need. And then we go back to business as usual. But healing doesn’t end with the funeral; indeed, it barely begins there.

We tend to approach conflict the same way. When we can't avoid or deflect it, we seek to de-escalate quickly: We try quickly to reassure or appease or cajole, striving for safety over honesty, or else we offer immediate mediation. As soon as a situation has cooled, we consider our work finished. But really we’re just beginning.

It’s only when you’re out of immediate crisis response that you can begin to think about Recovery. This is where we move from chaos to cohesion, and restore a sense of safety and predictability. It's the point in which we can pause and take stock: "Did that really happen?"

In order to move forward through grief, you must first acknowledge it. That also requires that we name all of the attendant harms that happened.

I still distinctly remember the feeling of sitting down at those first Dinner Party tables, and saying out loud things I’d never said shared with anyone. I realized then what most people realize when they open up about things they’d kept under lock and key: Speaking a truth out loud helped to release its grip on me.

And yet, our culture too often tells us to do the opposite: to avoid mention, lest we remind a grieving person of their pain. A couple of years ago, I spoke with a clinician who expressed concern about peers openly talking about loss and trauma – better, he thought, that we reserve that kind of talk for a therapist's office. But when our mental health care providers are over-saturated with demand and often financially out-of-reach, that kind of thinking is a prescription for silence. What's more, it paints as dangerous the very thing that can help us find healing. Without creating space to name and move with grief, it’s apt to fester in quiet.

“People don’t resist change. They resist loss.” So goes an oft-quoted adage by Harvard professor Ron Heifetz, in his seminal book, Leadership on the Line.

Managing a crisis is of course different from managing any other form of change, and we'll dig more into the latter in a future post. But we'd argue the same principle applies to both: Helping someone move through grief or any other form of loss – which is to say, change – requires first naming and acknowledging the reality of what's happening. Similarly, leading any group or groups of people through change requires taking seriously what’s at stake for them: the people they might be letting down, the fears of what the change will mean. When we’re met with resistance, it’s natural to try to convince someone of all the reasons things will be better on the other side. We justify, we explain away, we insist on moving on. But that line of reasoning often falls on deaf ears, or backfires altogether.

For years, I felt haunted by a particularly bad episode in my tenure with The Dinner Party. I wanted so badly to be able to move on, lest it cast a shadow over some of the most important experiences of my life. Yet I found myself returning to that moment, as if on a loop – confronted by innocuous reminders, fearful of situations that bore only the faintest resemblance to what had happened, trying continuously to make sense of aspects of which I remain, even now, a little in the dark. I struggled to release certain relationships from the wisps of resentment and anger that lingered, and longed to free my own body of shame, and of the loss of trust.

I'd felt like the fall guy (even now, I want to take out the qualifier – I was the fall guy). That meant that I struggled to fully examine my own sources of culpability: to admit any measure of responsibility risked taking on a responsibility that wasn't mine to own. But fixating on the ways I felt wronged meant that I couldn’t fully absorb the lessons of that moment. I’d screwed up, too; I needed to work through my feelings of hurt in order to let that be a part of the story, without it becoming the whole story.

And then last Fall, K and Mary, both colleagues then and now, came over. We got to talking about that chapter, in part because it remained so front of mind for me. “I need y’all to confirm for me that it really was that bad,” I said. Without missing a beat, they both replied, “It really was that bad.”

We talked about everything that had happened. Crucially, when I repeated something someone had said to me at the time, K gently corrected me. Memory is famously faulty, especially (and counter-intuitively) when it comes to the moments we’ve relived again and again. In my mind, I’d replaced one word said with another. It changed the meaning – not hugely, but enough to matter. Naming isn’t just healing; it can give us a window into the ways our perspective has distorted the truth.

And sure enough, after that conversation, it no longer felt activating to think about that period. That one bad episode became just that: one bad episode, right-sized alongside all the other episodes, good and bad and everything in between.

Naming and acknowledgement is crucial, in the endless – and endlessly changing – road that is healing after the loss of someone significant. The same is true of any form of loss. And owning our piece of the mess is easier done when there is space to name whatever grief we carry.

Then finally there’s the question of long-term Renewal. Renewal is where we begin the work of meaning-making and reclaiming newfound purpose, of post-traumatic growth and reimagining the systems we interact with, of forging new and deeper connections and friendships.

Most people who've experienced major loss have examples of friendships that faded or disintegrated in the face of grief. But as my Dinner Party co-founder puts it, grief can also be your entry-ticket to a “cosmic motorcycle club,” producing some of our most meaningful friendships and relationships. We would do well to think of grief not as something to be overcome, but as generative tissue: a binding agent that can be every bit as connective as it can be disconnective. (To hype a recent post of TDP’s, “grief is not a boundary – it’s a bridge.”)

Want to deepen social cohesion? Look to shared pain-points.

Over the last several years, we’ve been working to build The Parents’ Network, a community led by and for parents whose children have experienced internet harm. In April, I gathered with more than 50 families who’d lost a child to causes ranging from cyberbullying to TikTok challenges to fentanyl poisoning and an illegal drug market that has exploded thanks to Snapchat.

They hailed from dozens of states, ranging from Louisiana and Alabama, to Oregon and California, to New York and Pennsylvania. Over pizza one afternoon, I watched a group of a dozen or so dads crowd around a table in a small grey courtyard in the back of the Marriott in Midtown. Their jobs ranged from rancher to educator to chicken farmer to business executive to insurance salesman, and who knows what else. Their voting habits surely differed, but here, it didn’t matter. They were “the Archewell Dads” – their self-proclaimed moniker, named after the foundation that made this work possible. What bound them together was a transcendent identity, borne of shared grief.

It was a group of people who would never otherwise find themselves in the same room, let alone around the same table. That they could be friends – and indeed call themselves brothers – sounds fantastical in a moment when pluralism is profoundly imperiled.

If you’re a nerd about these things (hi, reader), you’ve probably heard someone say something to the effect that pluralism works better when it’s about action and not just words. Want to deepen relationships across difference? Engage in collaborative problem-solving.

Meh, okay. Sometimes. It’s true: To engage this group in a dialogue circle about why they believed what they believed would have generated benign curiosity at best, dismissiveness or rage at worst. And it’s a non-starter anyway: no one would’ve shown up to that conversation to begin with.

The problem is that shared action alone rarely yields deep enough bonds to withstand heat. Someone blows up in a meeting; you know in passing that they’re caregiving for an aging parent, but “get it together,” you think to yourself. They're treated with kid-gloves at the next meeting, and after a few more, they leave. You help paint a mural at the local elementary school, and meet a fellow parent there. You become Facebook friends, and recoil when they next post. You give a passing nod at the next family night, and otherwise avoid them.

When friction occurs, when things go off the rails – and things will, eventually, go off the rails – what do you have to fall back on?

If you want to deepen social cohesion, you'd do well to find a shared pain-point – one that’s personal and powerful enough to motivate shared action, and which elicits not sympathy but empathy, allowing the members of that group to claim a transcendent identity.

But that sounds messy, right? After all, "Crises often amplify stress and unresolved emotions," write our friends at SCRR. That means that emotional activation — intense reactions triggered by stress, grief, or trauma — is unavoidable.

The thing about working with grieving people, or building belonging around shared pain-points, is that – at some point – something will inevitably go a little off the rails. That’s actually the beauty of it.

When we expect discomfort, we’re less likely to freak out about it. We’re ready for it, which means we can normalize it: People are more apt to give each other grace when they, too, have felt those same big feelings. Those experiencing dysregulation are buffered from a shame spiral – it’s easier to recover when you know you’re not alone.

It also means that grief literacy has to be baked into a community’s core ways of working with one another.

Grief literacy as a set of organizing tools

As noted, grief activates our stress responses: It can affect us physically, changing our sleep patterns and our appetite. It affects us emotionally, eliciting sadness or anger or sudden or exaggerated reactions. It affects us mentally, producing brain fog and impeding our executive function skills, and socially, driving us to self-isolate, often unable to find pleasure in the people or activities we used to enjoy.

Tending to its hallmarks means knowing how to pre-empt them where you can, by carving out time and attention to help people understand and manage their triggers. It means putting a cultural premium on self-care, so that people can refuel their tanks when they find themselves depleted. It means developing shared language and tools to create and maintain healthy group dynamics, helping groups and the individuals within them to understand their own and others' activations, and the ways they're primed to interpret particular actions because of our past experience. It means learning how to navigate conflict in healthy ways, and how to respond to harm or hurt in real-time, without shaming someone.

For the last several years, our work with The Parents’ Network has given us a front-row seat to the fight for tech reform and digital safety: a fight driven largely by bereaved moms who've lost a child to internet harm. Dig deeper into any reform movement, and you’ll quickly discover: Grief has produced some of the world's most unrelenting advocates and change agents (see: Mamie Till, Lucy McBath, the Parkland students, every climate change activist motivated by eco-grief).

To view grieving people only as objects of sympathy is to ignore their power. And yet, too often, we encounter organizations whose advocacy efforts are stymied by interpersonal drama, which has, at its root, untended grief or trauma.

We believe that the people who've lived problems are often the best equipped to solve them. But if we are to engage people in work that is both professional and personal, we have to be ready to hold space for grief and all that it brings up.

Creating cultures of care that hold together when it counts depends on grief literate leadership. In the era of polycrisis, any community-builder would be well-served by it.

What’s grief got to do with it? It turns out: Everything.

—

Author: Lennon Flowers (bio)

Thank you, Lennon, for this profound piece on why grief literacy is essential for leaders, especially now.

I've long admired your capacity to honor the full range of our humanity in community-building work. What strikes me most about this piece is how you make the case that grief isn't something to "get past" in order to do the work — it IS the work. The connection between untended grief and our inability to stay in relationship with each other feels so urgent right now.

Your point about funders struggling to see the relevance particularly resonates. When people are adopting a problem-solving lens, they often can't see how our emotions and lived experiences are central to addressing our most important challenges. The courage you and your team show in standing for experiences like grief — which profoundly shape us — feels like such necessary leadership.

The progression you describe from grief to isolation to anger to a desire to dominate maps onto so much of what we're seeing in our fractured public discourse. It makes me think about how many of our attempts to "bridge divides" skip right over the grief piece — the losses people are carrying that make it feel impossible to stay curious about each other.

Thank you for this framework and for continuing to model leadership that is deeply human. It helps me think about my own work.

Your point around shared pain-points (as opposed to just shared action) reminded me of something I read earlier this week from Marshall Ganz: "Most of us have had moments of hurt or we wouldn't believe the world needs fixing. But if we hadn't had moments of hope, we wouldn’t be trying to fix it."

Both speak to how communities can form a transcendent identity — one that arises from hurt but is sustained by hope. It's almost aspirational: an invitation to be part of something bigger than ourselves.