How dare they? (Alt: The WTAF Test)

By Lennon Flowers

My mother-in-law is a writer and an actress. For the last three years, she’s been working on a one-woman show. A little over a year ago, I saw a workshop of an early version of it. It was terrific. I’ve met enough actors to know they crave affirmation. (Don’t we all?) So of course, I immediately told her I loved it. In the passenger seat on the long drive home, I wrote a many-paragraph text about why: the specific things I loved, the bravery and courage I so admired, the things she was wrestling with in public that I wrestled with too. I sent it, and never heard back. I remember feeling a little disappointed: What, not even a heart button? But I figured she was busy, no big deal.

A year later, she and I went out to dinner. At one moment, downtrodden, she said, “Well, I know you hated my play.” I was taken aback. “What do you mean?” “Well, you just didn’t seem that enthusiastic, and I didn’t hear anything from you after the show.”

“Did you get my text?,” I asked. It turned out, she hadn’t seen it. I pulled it up, and she read it at the table. Sure enough, she felt relieved and affirmed.

For a year, she had operated on the assumption that I didn’t say anything, and that I hated her play. I operated on the assumption that she had seen my text and not bothered to respond.

How often do we make assumptions based on faulty or incomplete data, and then start to feel a certain way about someone based on a false perception?

Everyone does it. We fill in gaps in actual information with assumptions. We’re meaning-making creatures, so we make a certain meaning of those assumptions, and then draw a false conclusion based on that inaccurate information.

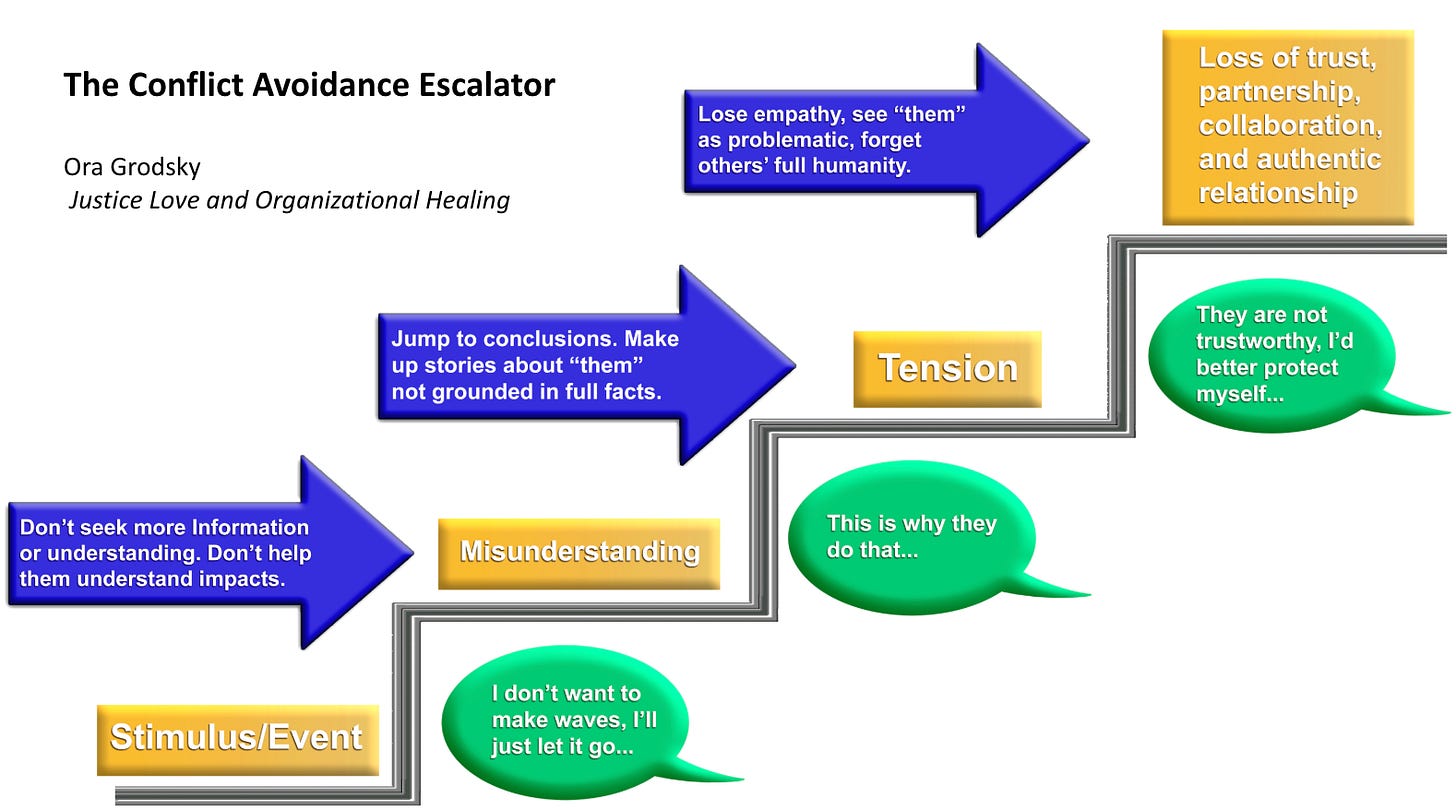

My friend Ora calls this the “conflict avoidance escalator”.

The boxes are what we experience, starting with the original event. The thought bubbles are the stories we tell ourselves based on our perceptions of what happened. The arrows are the actions we take, or don’t take, based on the conclusions we’ve drawn. The actions that we take escalate further misunderstanding, tension, and eventually, a loss of trust and authentic relationship.

How many conflicts mirror what happened with my mother-in-law? Something happens. We don’t want to shame someone or cause a fuss, so we just move on. But we start to unconsciously develop a story: This person doesn’t respect me or my time. The next time we interact, we’re mealy-mouthed; we hem and haw rather than naming our needs, because we already assume we can’t count on them.

But if we’d actually had a conversation at that first moment, we would have realized that there was an explanation for it. (Indeed, perhaps something as simple as a missed text.) In other situations, the explanation might elicit compassion or empathy or forgiveness; at the very least, we would learn that it wasn’t personal. Perhaps the conversation would reveal something important about our own piece of the mess: our own failure to communicate properly, or something else that we could correct for next time.

The “How Dare You” Test

“When the going gets rough, turn to wonder.” So goes one of our favorite “Touchstones” from Parker Palmer and the team at the Center for Courage & Renewal. “Turn from reaction and judgment to wonder and compassionate inquiry,” they go on. “Ask yourself, ‘I wonder why they feel/think this way?’ or ‘I wonder what my reaction teaches me about myself?’”

We humans are notorious for confirmation bias: We enter a conversation or a relationship with a particular bias or assumption, and subconsciously look for data that confirms our underlying belief-sets. As our pal Scott Shigeoka reminds us, checking that impulse – and choosing to exercise curiosity instead – can unlock transformative effects in our relationships.

I was recently talking to a longtime friend and colleague, with whom I’ve navigated some tricky territory over the years, with more than a little scar tissue to show for it. She asked me for something that I felt, given our history and the context, was inappropriate. I felt myself getting hot.

“How dare she?” I thought to myself. There was no acknowledgement of our history with this particular subject, of the ways those wounds still lingered, or the power imbalance in our positions. If she’d paused to consider how that might land, I’m certain she would have thought better of the ask, or at least named why it might be complicated. There it was: The line of code in me that longs to be seen – that is quick to read disrespect into a situation – was activated.

But she wasn’t thinking about that. She had all kinds of needs she was tending to – in this case, all equally legitimate to my own. She was doing right by someone else, even if I felt triggered by it. We don’t have to be right to think we’re right.

Since then, I’ve been catching myself: When I think to myself, “How dare they?” it’s a cue for me to investigate my own reaction, and to name what’s coming up for me. More importantly, it signals there’s something about the other person’s motivations that I’m missing: What need is being served here? If I can uncover that, I can figure out another path to finding common ground, or at least acknowledging the humanity behind their position.

It doesn’t always work: Some actions are, of course, callous or cruel or vindictive or careless. But more often, people find a way to self-justify what they’re doing. I don’t have to agree with it, but if I have to negotiate through their resistance, or find a way to get unblocked, I do have to understand what’s important to them and why.

To be clear: Explanation is not the same as excuse. Understanding our own or each other’s lines of code doesn’t absolve us of responsibility when we get activated, or spare us the need to apologize, or to work toward repair.

And neither does it make us immune to relational irritants. I can try to understand a person’s underlying motivations — the reasons they have calcified into a particular position, the sources of pain that made them liable to inflict the same, the way we’re apt to falsely assign blame — and still find myself super annoyed, or disappointed by what they did or didn’t do.

The point is not to tie this in a bow, but to say, simply, that understanding those things slows down my impulse to run away or discard. It asks me to consider another interpretation than my most instinctual one. If I’m primed to read things through the lens of, “they’ll never understand me,” or “I’m always left out,” or “people always let me down,” or “I can’t let anyone see me as weak,” then chances are that’s how I’ll code whatever situation I find myself in. The challenge is to gather additional data to see if there could be any other interpretations.

I was leading a workshop recently for a group of parent leaders in The Parents’ Network. One of the moms shared that she calls her version the “WTAF test”: “Whenever I catch myself thinking, ‘what the actual f***’ in response to someone’s actions, I know to get curious.”

If the situation warrants holding onto a little judgement, asking yourself “I wonder why he’s such an asshole” can help you at least start to exercise the muscle.

Recognizing our lines of code

Email and text messages rob us of facial cues or voice intonations, so it’s easy to draw false conclusions from them. While hearing a voice or seeing a face can help clear up the confusion, it can also, of course, compound it. I had to learn to consciously relax my eyebrows on Zoom calls, because – as a colleague once pointed out to me – it turns out my concentration face closely resembles Resting Bitch Face.

It proved a useful lesson to me: Our body language communicates messages even when – especially when – our words don’t. What we’re saying often matters less than how we’re saying it.

“People consistently pick up on warmth faster than on competence,” writes Amy Cuddy, a professor at Harvard Business School, in a joint paper with the co-authors of Compelling People: The Hidden Qualities that Make Us Influential. If you want to get better at conflict, becoming more aware of the nonverbal cues you’re sending at any given moment is a good place to start.

But we’re also coded to receive certain information in a certain way: Our identities are shaped by the messages we’ve received and internalized. Our past experiences inform what we’re likely to perceive in the present. We each carry around a particular set of emotional needs – longings for validation, or affirmation, or credit, or visibility, and trip-wires that make us particularly reactive. (Question my integrity, and I will bludgeon you with it.)

That means we have to pay attention to the histories we each bring into any room, and all the histories we cannot see within it. It’s why paying attention to issues of power and positionality in a conversation matter for anyone interested in working with other humans: What might feel totally benign for one person might be activating for another. We obviously can’t always know each other’s histories, but we can pay attention to cultural patterns that mirror patterns of discrimination, ensuring that the voices heard aren’t only the ones who are accustomed to being heard.

(Even if you believe that “pluralism” has rightly supplanted DEI as a focal point on college campuses and everywhere else, that point still stands. It’s bonkers that all of our uproar and backsliding over DEI has made that controversial right now, but we’ll come back to that in a future post. I digress.)

In this era, our language, too, is highly coded: the same words mean vastly different things to different people depending on their news sources. Recently, a friend in Jacksonville was told that using the word “belonging” was like “waving a red flag in front of a bull.” I remember an early partner in The People’s Supper telling me to be careful of using the word “folks” in conservative company, because President Obama had regularly used it. AYFKM. And: Fine. Tailoring your language to your audience without understanding that audience can feel pandering. But done well, it can help ensure you’re heard.

Tuning into our “lines of code” is a core tenet of non-violent communication: Understanding which of our “universal human needs” are motivating a particular action or reaction in someone else can help us replace judgement with empathy. (In all honesty, we might find ourselves judging them anyway. But acknowledging the fears or needs behind the words can soften a conversation, whereas dismissing or ignoring the underlying need can inflame it.)

Understanding our own lines of code and which emotional needs are exaggerated in us can also help us take responsibility for our own behaviors when our reactions are outsized to the situation at hand.

I recently found myself waiting for a response to an email. As one hour became five hours and one day became four days, I started to lose my mind.

It was, admittedly, an email with semi-urgent action items and significant implications. I’d emailed the same recipient once before, with no response. At the time, I’d chalked it up to busy schedules and competing priorities. After all, who among us hasn’t missed an email, or neglected a response? There have been plenty of times where I let an email sit until I had capacity to adequately address it, only to let it slip beneath the constant stream of inbound asks. No hard feelings, right?

But this time, whatever other explanations were at play all seemed secondary: This was the height of disrespect. I projected onto the silence every other moment of feeling slighted. (As a kid from the South living up North — a plebeian who has come to intimately know the well-heeled ways of the donor class — this is a familiar feeling.)

As I waited impatiently for a response, I flashed back to a professional shit-storm a decade before, when fraying relationships imploded in spectacular fashion: the feeling then of repping the organization with the least money doing the most work, the watching for slights, both real and perceived. I told a colleague about the delay. On cue, she said it seemed rude. I felt vindicated.

Within a few days, I finally got a response. Once again, the explanation had to do with busy schedules and competing priorities.

Meanwhile, however, I’d let my own misinterpretation fester into a larger story, fueling my mistrust of someone with whom I needed to build good rapport: Our ability to collaborate effectively depended on it.

When in doubt, ask

Okay, but you can’t expect someone to always be self-aware of the verbal and nonverbal messages they’re sending. Yes, our stories can be revealing, helping us to complicate the narratives we carry of one another, and to illuminate our invisible identities. (It’s why we’re such big fans of personal story-sharing over shared meals as a means of bridge-building.) But most of the time, you have to earn someone’s trust before they’re willing to share those kinds of stories.

Even then, most of our lines of code are obscure even to the people who know us well, let alone the casual observer or professional acquaintance. (Hell, if you’ve never had a good therapist – and most people haven’t – you probably don’t understand your own “lines of code”.) Most of the time, we don’t know the histories another person carries into the room.

So in the absence of that information, what can we do to get more data, or at least curb our impulses to falsely interpret?

The obvious answer, of course, is to ask. But that’s easier said than done.

It’s true that we very rarely take the time to slow down a conversation and check our understanding. There are lots of reasons for that: Chalk it up to a culture that places a premium on efficiency, or technologies that profit off of outrage, or simply the way our social muscles have atrophied.

Perhaps the most likely culprit is simply that it feels uncomfortable. We fear we’ll be met with defensiveness. We fear we’re missing something – that what’s happening should be obvious. We think we’re avoiding conflict, only to inadvertently deepen it.

Or maybe our own lines of code have already been triggered, so we’re in fight or flight mode: Our capacity to self-regulate is shutting down. We’re already pissed, so any explanation they give will land on deaf ears. We fear that by giving one person grace or the benefit of the doubt, we’ll be betraying another.

Yes, if there’s any chance we’re misinterpreting someone based on limited data, we’d do well to ask for more. But what do you do when that feels like an unavailable option?

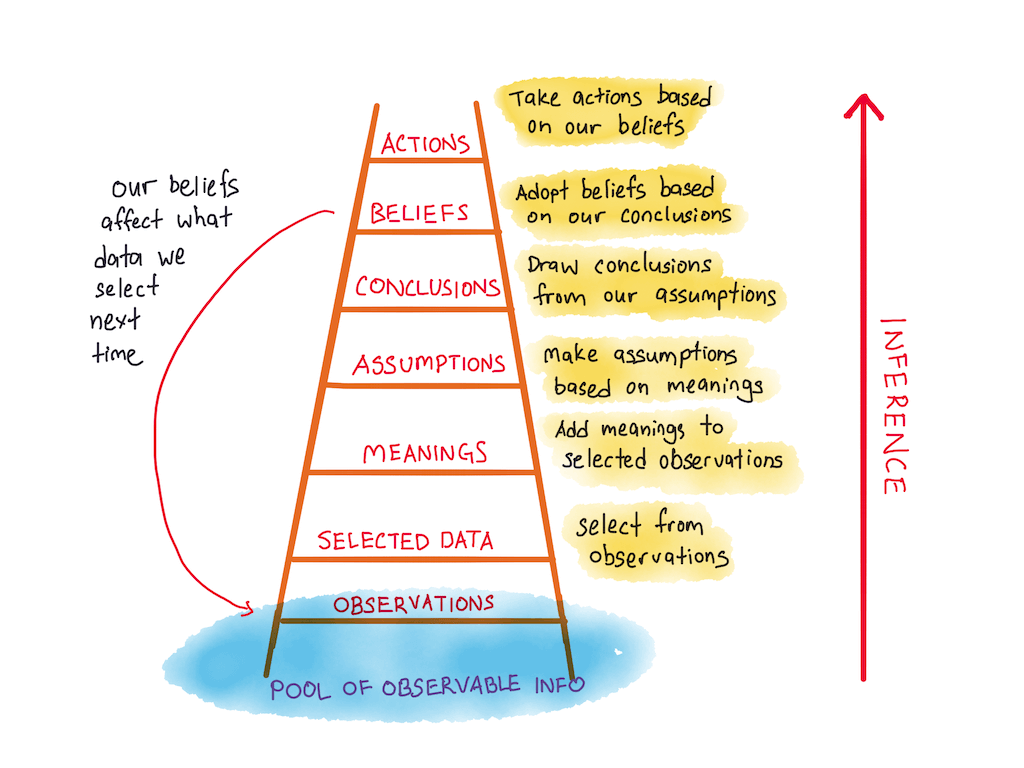

Ladder of inference

The ladder of inference is a tool first developed back in the 1970s by an organizational psychologist named Chris Argyris, and popularized by Peter Senge in his seminal book on leadership and organizational learning, The Fifth Discipline.

(A micro-case in point: I haven’t read the book or anything else by Peter Senge, but I did see on the internet that it sold a lot of copies, so I’m trained to insert the word “seminal” into that sentence without thinking about it, and to convey to you, good reader, that I am an informed subject matter expert. But I digress. Again.)

The ladder of inference illustrates the process by which we often leap to conclusions based on incomplete data: our tendency to selectively pick data that conforms with our existing beliefs, and to impart our own meaning on it. It explains why two people looking at the same piece of information can draw such different conclusions from it – which in turn explains why we have such a hard time arriving even at a consensus reality these days.

If we’re to overcome our natural hesitation to ask for more information, we have to first recognize there’s something we might be missing, and to entertain the possibility that we’re acting based on a conclusion derived from a false assumption.

As I sat waiting impatiently for a response to an email, I needed to heed my own lines of code. What part of my reaction was due to the delayed response, and what part of my reaction belonged to a past pain-point?

The feeling – of being ignored, or treated as less than – isn’t one I can easily escape. Perhaps the best I can hope for is that knowing those things about myself can, with time, afford me the ability to hold that feeling as just one interpretation among multiple explanations.

The more intimately acquainted we are with our own patterns and reactions – the way we stiffen at a particular word, the speed with which we dismiss a particular idea – the easier it is to interrupt that response in the moments when it doesn’t serve us.

Knowing there’s a ladder and that we might be on it can help us pause long enough to get more data.

—

Author: Lennon Flowers (bio)

I’d say there isn’t one session that goes by with a client where we aren’t talking about _some_ version of this: how “the absence of information is filled with dirt” and how to gain more proximity to truth using tools like “the story in telling myself is…but please reality-check me — is that right?”

Fun to see another framing here + these interventions. I deeply believe it is almost impossible to be in judgment at the same time as being curious. To shift into deep, genuine inquiry and curiosity is a gift to, and for, humanity.